The paradox of utopias is that while their failure is assured, their appeal is eternal. 800 years ago, tens of thousands of ordinary people left their homes, their families, and the innumerable small ties which made up their lives to march on Jerusalem and retake it in the name of God, in the deadly mass migration known as the Children’s Crusade. Today, would-be jihadists make the dangerous journey to Syria and Iraq, where they hope to join the forces of the Islamic State and erect a global caliphate. Similarly, during the sixties and seventies thousands of young Americans flocked to the People’s Temple, a radical church dedicated to building a post-racial heaven on earth. That dream concluded with the death by poisoning of 909 people on a commune in Jonestown, Guyana on November 18, 1978.

The paradox of utopias is that while their failure is assured, their appeal is eternal. 800 years ago, tens of thousands of ordinary people left their homes, their families, and the innumerable small ties which made up their lives to march on Jerusalem and retake it in the name of God, in the deadly mass migration known as the Children’s Crusade. Today, would-be jihadists make the dangerous journey to Syria and Iraq, where they hope to join the forces of the Islamic State and erect a global caliphate. Similarly, during the sixties and seventies thousands of young Americans flocked to the People’s Temple, a radical church dedicated to building a post-racial heaven on earth. That dream concluded with the death by poisoning of 909 people on a commune in Jonestown, Guyana on November 18, 1978.

The nightmarish quality of these events obscures their participants. Leigh Fondakowski’s Stories from Jonestown is an attempt to reveal the people of Jonestown, and to understand what brought them there. Fondakowski spent three years interviewing former members of the People’s Temple for a play about their experiences. She has concluded, wrongly, that the process of writing a play about Jonestown would interest the reader as much as the events of Jonestown themselves. Nevertheless, the book is an intimate portrait of the People’s Temple from the perspective of its members, and a valuable study of the cult mentality.

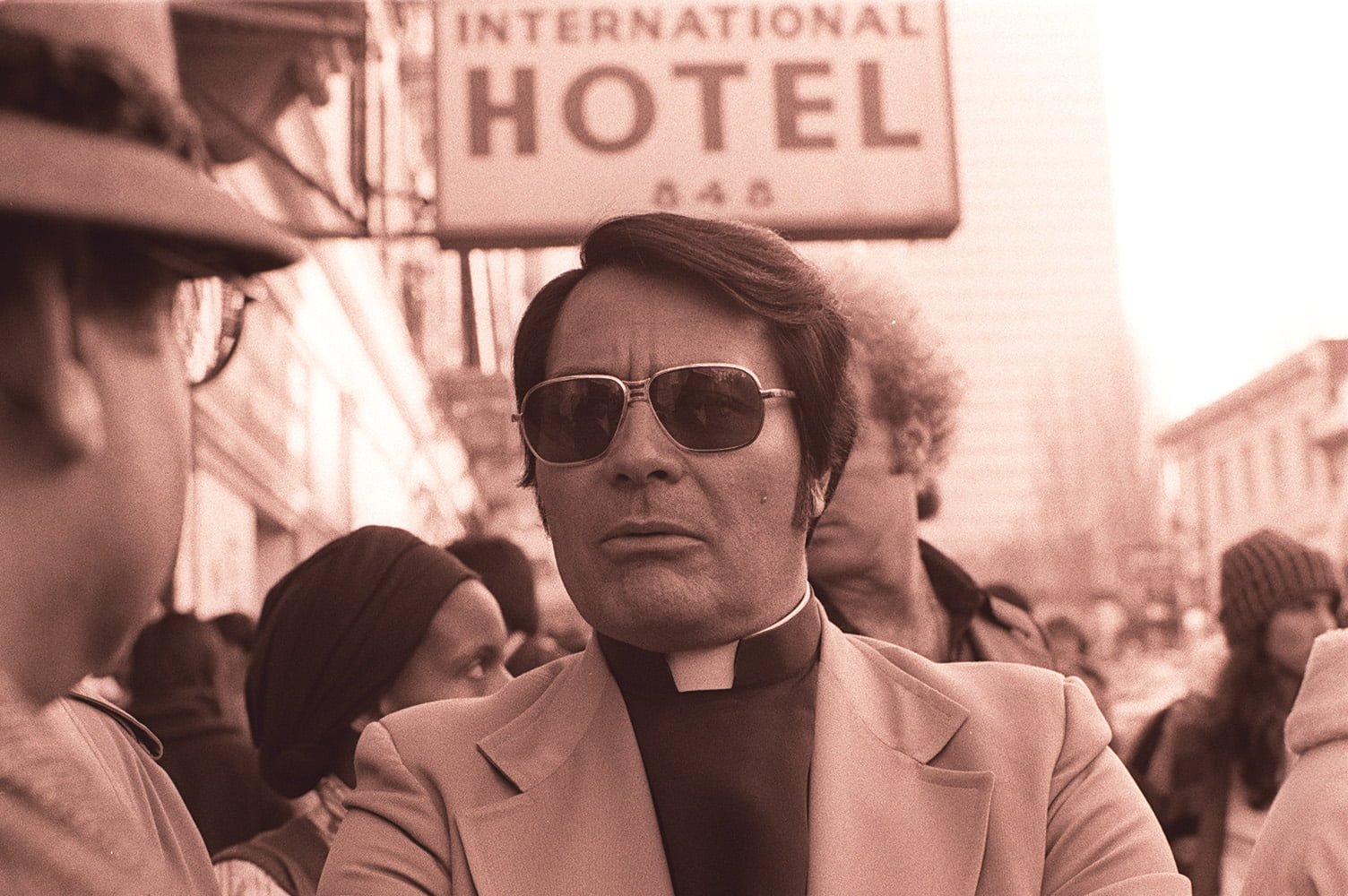

By necessity, the book is dominated by the absent figure of the man who gave Jonestown its name. The Reverend Jim Jones founded the People’s Temple, and his disturbing, electric presence dominates many of the narratives in Stories. “When Jones finally agreed to meet me,” the journalist Julie Smith remembers, “he was sitting on a throne, surrounded by about ten of his followers. When he stood, the rest of them stood, as if at a prearranged signal. Swear to God, the hair on the back of my neck prickled, something that usually only happens when I see a spider. That’s the point at which I thought, ‘Something really wrong is going on here.’”

Jones often employed these manipulative, theatrical set-pieces. Before his marathon sermons he would conceal bags of ox blood under his armpits, with catheters running from them down his arms underneath the skin. At dramatic moments in his sermon he would squeeze his arms to his body and make the blood run from his palms in ersatz stigmata. Members of his inner circle would eavesdrop on new arrivals to the congregation and write what they heard on index cards, to be smuggled up to Jones, who would then startle the newcomer with a display of psychic ability. Jean Clancey was one of those who smuggled the cards up to Jones. At the time, she told herself that Jones would have exhausted himself had he had to use his psychic powers on everyone, but that some of his feats were undoubtedly genuine. She tells Fondakowski, “you can tell yourself anything.”

Jones grew up in poverty in rural Indiana, an intense child with a mop of dark hair who held elaborate funerals for small animals on his parents’ farm. In his teens he embraced Marxism, and became a student pastor at a Methodist church in Indianapolis. The church refused to let him integrate blacks into his congregation, so he left to start his own. He called it the Community Unity Church. There, he combined revivalist showmanship with radical politics, pretending to pull tumours from the bodies of the sick and delivering animated sermons emphasising the most egalitarian passages of the New Testament while viciously denouncing the rest. Indianapolis proved hostile to radical Marxist theology, so Jones had a vision that it would be destroyed in a nuclear attack. He moved the church to Redwood Valley, California, and renamed it the People’s Temple. It was only one of the hundreds of utopian communities that dotted California during the 1960s, but it was unique, not just because it blended Christianity, socialism, and integrationism, but because at first it did so successfully. Young idealists looking for a new way to live came to Jonestown and found blacks and whites of all ages living together in a way that had previously seemed inconceivable. Membership rapidly expanded. Offshoots opened in San Francisco and Los Angeles, and a fleet of thirteen buses ferried people back and forth from the Redwood Valley commune to raucous services in the cities.

Those who had experienced the brutality of American racism first-hand were particularly susceptible to the appeal of Jones and People’s Temple. Vernon Gosney, a white man, was nineteen when he met his wife, a black woman named Cheryl. His family disowned him. The young couple became involved with People’s Temple, one of the only places in 1960’s San Francisco where an interracial couple could be unconditionally welcomed. They eventually drifted away from the church, but then Cheryl fell pregnant, was given a botched caesarean, and fell into a coma from which she never awoke. Gosney brought a medical malpractice suit against the hospital. At trial, the doctor, unrepentant, testified that he couldn’t tell that Cheryl had lost oxygen because she was “too black”. The jury found for the doctor. Gosney concluded that “everything that Jim Jones said about the United States is true.”

Gosney subsequently followed the People’s Temple when Jones moves it to Guyana, only to find that its promise of a post-racial utopia was a cruel illusion. During the final massacre he was shot in the liver and the spleen, and only survived by hiding in the jungle for nineteen hours. The Guyanese soldiers who loaded him into the cargo plane bound for the military hospital in Puerto Rico stole the shoes off his feet.

The Jones revealed in the book is a visionary, an idealist, a sociopath, and a paranoiac, convinced that the US government is bent on his church’s destruction. Once in Guyana, he grows more erratic. He keeps a briefcase full of needles and barbiturates by his side at all times. He wakes up the community in the middle of the night, ranting over loudspeakers that they are under attack, commanding everyone to take arms and defend the perimeter. These “White Nights” grow more frequent. When Congressman Leo Ryan makes a fact-finding mission to Jonestown at the urging of concerned family members, Jones takes it as a fulfilment of his darkest prophecies. Nevertheless, he commands his followers to show Ryan a welcoming face. That night, they hold a communal meal in the central meeting hall. The Jonestown Express, the community’s soul band, plays the hits. A visibly overwhelmed Congressman Ryan speaks, declaring that “from the few conversations I’ve had with a couple of folks here already this evening that whatever the comments are, there are some people here who believe that this is the best thing that’s happened to them in their whole life.” The hall explodes in applause.

The next day, however, the mood is tense. Ryan, his aides, and a crew of journalists are on a tour of the community when Edith Parks, a member of the congregation, walks up to the Congressman’s aide and tells her “I am being held prisoner and I want to leave.” It’s the first indication that something is wrong. Over the course of the day, more people come forward and demand to go with the Congressman. In a detail so filmic as to seem implausible, clouds gather, thunder rumbles, and it starts to pour. The Congressman is heading to the airfield with the defectors when Jones sends a group of young men after them with automatic weapons. They shoot everyone in sight, and the only survivors are those who manage to hide under the dead or crawl into the jungle. Then comes the final assembly, the recriminations, and finally, the notorious Kool-Aid, which was not really Kool-Aid but grape-flavoured Flavor-Aid mixed with cyanide in a metal tub. Some drink it voluntarily, others need to be held down. One of Fondakowski’s interview subjects describes seeing someone squirt a hypodermic needle full of poison into her baby’s mouth before she flees into the jungle.

In the book’s epilogue, the survivors come to see the play that Fondakowski has made of their experiences. Afterwards they congratulate her and say nice things, she dutifully records them, and we are meant to understand that some closure has been attained. But this tidy, American ending is immediately followed by the names of the 909 dead, which take up nine full pages at the end of the book, 909 people whose tragedies are only compounded by the experiences of those who survived and were irrevocably tainted by their association with the tragedy. Take Jim Jones Jr., the black adopted son of Jim Jones. Jim Junior was 18 when his entire family perished in Guyana. He ended up in San Francisco, working as a courier. One day his boss makes a joke about Jonestown and Jim Junior snaps at him, revealing his identity. The boss fires him immediately. Jim Junior recalls stalking the streets of San Francisco, a teenager alone in the world and bearing his father’s name, thinking “my father always said if we came back we would be lepertized.”